Unlike a broken leg or dislocated shoulder, there is currently no consensus on what may leave individuals prone to becoming concussed. Coventry Rugby’s Head Physio Matthew Look is aiming to change this over the next three years, in a project that is nothing short of ground-breaking.

Concussion is the most common injury in professional Rugby Union according to injury surveillance data collected over 16 seasons across English rugby. In the short-term concussion is associated with a host of head and neck symptoms, some of which include headache, grogginess, and a sensitivity to noise and light. It also alters movement strategies, balance control and disrupts cognitive function resulting in reduced concentration and memory difficulty. Of even greater concern are the long-term consequences of concussion. Recently, evidence has emerged linking repeated concussion to long term deterioration of neurophysiology, early onset dementia and the dreaded CTE.

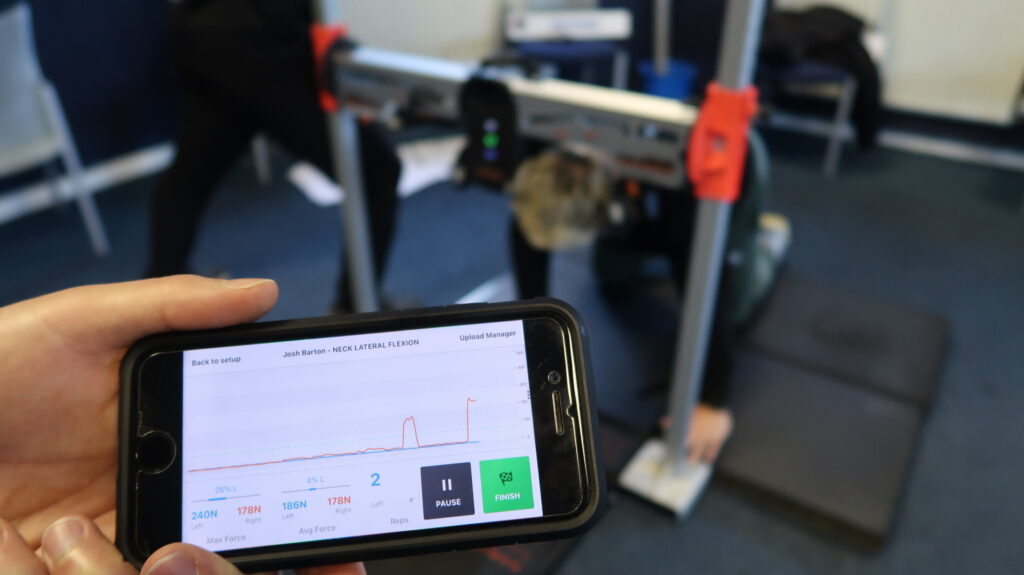

Having recently entered phase two of testing following last year’s introductory primary stage, the Coventry players have been in the club to carry out a repeated series of physical assessments that will aid Look’s mission to mitigate associated risks of concussion. In this secondary round of testing, Look has been assisted by Daniel Morgan, a leading Chiropractor in South Wales with extensive training in diagnostic ultrasound.

Morgan’s clinical expertise is being utilised to scan the deep lower back muscles, more specifically the Lumber Erector Spinae Group and the Quadratus Lumborum (QL). Morgan explained that there has been strong published evidence suggesting that there is a correlation between lower back muscle function and lower limb injury, and that more recently preliminary evidence has emerged suggesting there could also be a link between lower back muscle function and concussive events.

“What we’re trying to establish is the reasons why concussions occur – and if for whatever reason, some people are pre-disposed to them”. Coventry players are partaking in this series of tests that range from neck strength, muscle size, muscle function and activation levels. If it were to be discovered that a correlation exists between these variables and cases of concussion, that would go a long way in determining what could be done to minimise the risk of concussions occurring in the first place.

When asked where the project was at regarding its findings, Dan Morgan explained that the project is still in its early stages and that analysis would need to be done at the end of the season to see if any corrections do exist. The aim of the game will be to decide whether these variables are good, bad, irrelevant or lifesaving.

The clear end goal of the project is ultimately to identify any potential precursors to concussion. Once these are determined, interventions can be devised to minimise the risk of injury. This will keep players fitter for longer and improve performance and results over time. All this work, however, goes much further than rugby, and much further than sport itself. The project and its findings have the genuine potential to improve the quality of later life for anyone that has suffered concussive injuries, and possibly even save lives in the future – a result well worth any measure of testing.